Balzac’s cane and the miraculous ants

I recently made a phone call to ask a question I’d been too embarrassed to ask face-to-face. Here’s how it went.

“Hello, this is the Balzac Museum.”

“I have an unusual question for you.”

“Yes?”

“You know the cane in your museum that belonged to Balzac?”

“Certainly.”

“I remember visiting once and hearing a story about Balzac putting live ants in the top of the cane when he went out for a walk. Do you know anything about this? Can you tell me more?”

“No madame. I’m sorry, I don’t know anything about this.”

“Is there someone else at the museum who could help, a curator maybe?”

“Sorry madame. I don’t think there’s anyone here who could help with your question. I suggest you try our app. It has lots of information about Balzac.”

End of conversation. Just as well I didn’t tell her the whole story.

The Eiffel Tower, seen from Balzac’s garden

A visit to the Balzac Museum in Paris

Many years ago, I took an impromptu daytrip to Paris on the Eurostar to cheer myself up after a row. I was intrigued to visit the Balzac Museum, the former home of Honoré de Balzac. He’s probably best known as the author of the sprawling La Comédie Humaine series, which included around 90 novels and novellas.

I studied French and must have read Le Père Goriot at some point, but frankly have little memory of it.

The Balzac Museum is in Passy, in the 16th arrondissement, a well-heeled area with endless broad avenues of grand 19th century Haussmann buildings.

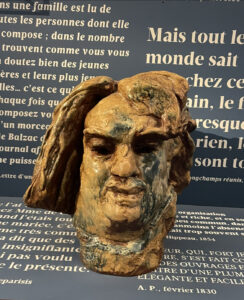

Rodin created this sculpture of Balzac’s head, capturing a moment of intense concentration

In this environment, the Balzac Museum stands out. When the author lived there, from 1840 to 1847, Passy was a village outside central Paris, in the countryside. You can still imagine how it must have been. A small three-storey house, with one storey at garden level and two storeys extending into the courtyard below.

A cottage-style garden half-way down a hill, with the land sloping down towards the Seine, less than half a mile away. When you stand in the garden today, you have a magnificent view of the Eiffel Tower across the other side of the river. But the tower was built between 1887 and 1889, so Balzac wouldn’t have had the pleasure of seeing it when he sat outside in his garden.

A prodigious appetite for work and caffeine

In truth, though, Balzac would rarely have pottered about his garden in daylight hours. He was famously nocturnal. Balzac would go to bed at 8pm each night, get up around midnight, sit down at his desk at 2am and start writing, powering through until 8am, sleeping briefly between 8am and 9.30am, then carrying on working until 4pm.

Balzac loved his coffee – up to 50 cups a day. This is his Limoges porcelain cafetiere

This unusual work schedule was fuelled primarily by caffeine. He averaged 15 cups a night, although there are rumours that he could drink up to 50 cups a day.

Thanks to his entertaining Treatise on Modern Stimulants, we know that Balzac devised his own “terrible and cruel” method for making Turkish coffee, which he recommended only to “men of excessive strength”. It involved adding a small amount of cold water to ground coffee and drinking it on an empty stomach.

“The paper covers itself in ink”

This devilish concoction had an immediate effect. In Balzac’s words:

“It blazes and shoots sparks up all the way to the brain. From then on, everything becomes agitated: ideas march like the battalions of a great army onto the battlefield where the battle has begun. Memories charge in, flags flying; the light cavalry of comparisons advances at a magnificent gallop; the artillery of logic rushes in with its convoy and its charges; witticisms appear like snipers; characters rise up; the paper covers itself in ink.”

Given his writing routine and the sheer quantity of caffeine racing through his veins, it’s no wonder that Balzac produced over 90 books.

Balzac’s cane: a handsome creature

Balzac did occasionally break out of his routine to visit boulevard cafes or attend the opera. He aspired to the elegance of a dandy and ordered a magnificent cane so that he would look the part in Parisian society. The cane cost 700 francs – more than the 650 francs annual rent he paid for the house at Passy.

Balzac suspected his cane had magical powers

The cane attracted a great deal of attention. Balzac wrote in a letter that his cane was the talk of Naples and Rome, and that everyone in Paris was jealous of it. He said: “Don’t be surprised if people tell you that I have a magic cane that produces horses, conjures up palaces and spits out diamonds.”

You can see the cane in the Balzac Museum – a handsome, flamboyant creature with a gold top, encrusted with turquoise stones. The gold top flips up to reveal a cavity. At the time, journalists and caricaturists wondered if the space contained a lock of hair or the portrait of a lover.

The story of the map-making ants

I have no idea why I returned from that day trip to Paris with such a clear story in my head about Balzac’s cane. I was convinced that Balzac used to fill the gold cavity at the top of the cane with ants when he went out for a walk. When he returned, he would shake out the ants and encourage them to walk through a small tray of black ink.

I don’t know precisely how you would persuade a troupe of ants to do that. I imagine ants are not easily herded. Unless, perhaps, Balzac used jam or honey to lure them towards the ink.

As the ants marched through the liquid, ink would gather on the bottom of their feet. Balzac would then encourage the ants to walk across a blank sheet of paper.

As they moved across the paper, the ants would recreate a map of the walk that Balzac had just taken. I appreciate that ants are not known for their ability to do this. Bees do it. They fly off, investigate the local landscape, return to the hive and perform a ‘waggle dance’ that lets other bees know where to find pollen, nectar and water.

Mind you, even bees don’t attempt this trick while confined in the gold stopper top of a writer’s bejewelled cane.

A hallucination?

Unfortunately, my ant story is improbable in so many ways. Balzac was a workaholic. Would a man with such a punishing work ethic really spend his precious spare time emptying ants into and out of his cane, using up good ink and writing paper in the process?

Over the years, I’ve looked into this mysterious story that has taken up residence in my memory. I can’t find anything to substantiate it. If you search online for Balzac and ants, nothing significant comes up. When I searched in French for Balzac and ‘fourmis’, the internet sent me to a site that offered treatments to get rid of carpenter ants in the village of Balzac in Poitou-Charentes.

La Canne de Monsieur de Balzac

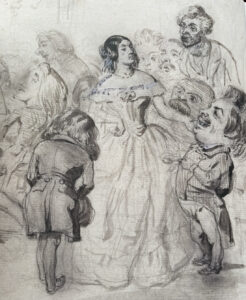

A contemporary caricature by J J Grandville, showing Delphine de Girardin towering above Balzac

I may have hallucinated the entire story. However, Balzac did joke about his cane’s magical powers and there is even a book inspired by the cane. In La Canne de Monsieur de Balzac, Delphine de Girardin writes about a literary salon in Paris where Balzac’s cane plays a starring role.

In the book, when Balzac holds the cane in his left hand, he is able to disappear. Under the cloak of invisibility, the author roams across Paris, observing the private lives of people who will become characters in his books. How else could he possibly understand the intimate secrets, passions and vices of his vast cast of characters?

Interior of the Balzac Museum

Earlier this year, I went back to the Balzac Museum in Passy. I stood on tiptoes in front of the cane in its glass box and squinted to see if I could detect any ant-like debris inside the gold top. No debris. No tiny footprints. Nothing.

When I was there, I couldn’t bring myself to ask the museum staff about Balzac and the ants. It felt like a foolish question. That’s why I rang up later instead.

I still think it’s a good story, though. And perhaps one day an enterprising entomologist will find a humane way to test out my theory. They can call their research ‘The cartographical powers of the Formicidae family’. They could test flying vs non-flying ants. Seriously, I think this idea has (ink-spattered) legs.

Discover more about:

- My one-to-one writing coaching and group workshops

- My work with charities

- My work with music clients