Litterature: turning rubbish into art

This blog explores two books and an exhibition that elevate abandoned shopping lists and scraps of paper into art.

Treasured rubbish

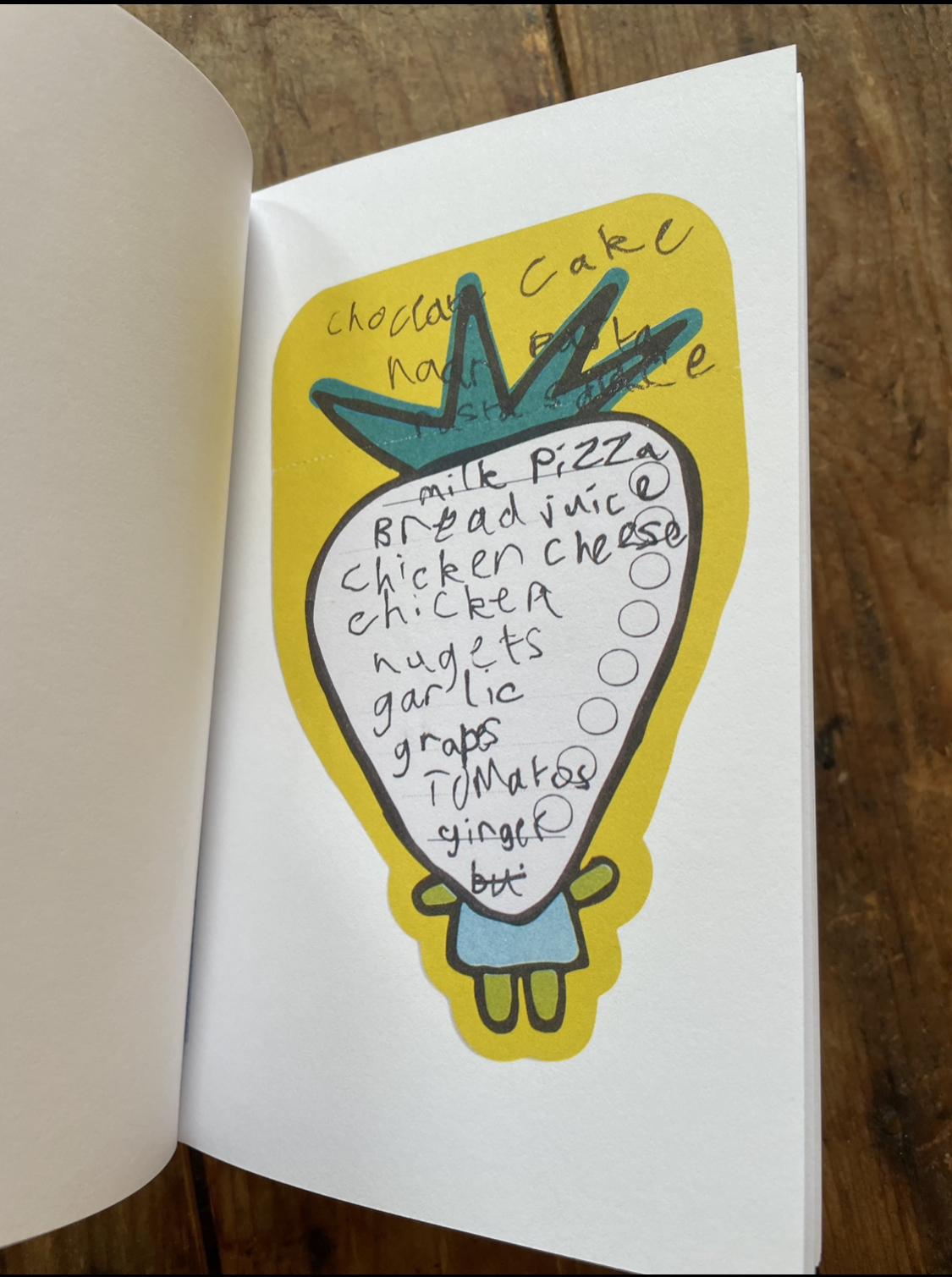

Have you ever been fascinated by a discarded shopping list left in a supermarket trolley? Wondered who the person was who just wanted to buy milk, bleach and a birthday card? There’s something so intimate about these scraps of paper that are thrown away yet offer a glimpse into someone’s life.

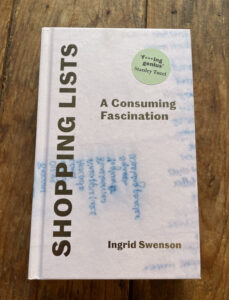

As Ingrid Swenson says in her new book, ‘Shopping Lists: a consuming fascination’, the items on the list, combined with the writing and paper can all say something about the shopper’s age, gender, dietary habits, nationality, profession, wealth and culinary ambition. They can give the observant reader clues about whether the person lives alone or with others, or whether they’re celebrating a special occasion or about to go on holiday.

Ingrid Swenson compares her love of collecting shopping lists to scavenging or foraging

Mozzarella, aubergines, custard

Swenson’s book draws uniquely on shopping lists dropped in a North London branch of Waitrose, which immediately suggests a certain type of clientele. Many lists are scribbled on neon Post-It notes. One is written on the back of some cello music; another is on the reverse of a rejection letter from a poetry magazine.

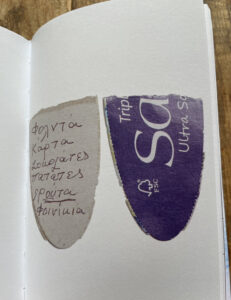

Different languages are scattered around. A list written in Greek is inventively squeezed onto an oval of cardboard from the top of a tissue box.

One way to make sure you keep the list short

A French list has ‘gingernuts’ in among the bread and grapefruit. One list in Italian includes a prosaic mention of ‘custard’ towards the end. You have to feel fondly towards the Italian cook who makes room for custard alongside their aubergines and mozzarella.

Swenson casts the activity of collecting shopping lists somewhere between scavenging and foraging. Not so different, really, from poking around in a neighbour’s skip or making a beeline for something sparkly at a jumble sale.

French rubbish

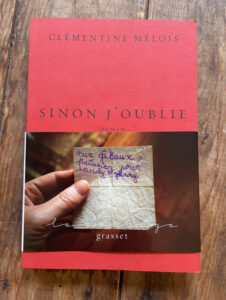

When Swenson’s book came out this summer, I was already attuned to the subject because a French friend had recently sent me a copy of ‘Sinon j’oublie’, a 2017 book by Clémentine Mélois. The title translates as ‘Otherwise, I forget’ or, more simply, ‘Checklist’.

Clémentine Mélois imagines the lives of 99 people who dropped their shopping lists

Following a similar obsession, Mélois collected 99 abandoned shopping lists and invented stories about the people who wrote them, giving each one a name.

I enjoyed the Georges Perec quote that appears as a preface:

“What happens every day and returns every day, the banal, the everyday, the obvious, the common, the ordinary, the infra-ordinary, the background noise, the usual, how to account for it, how to question it, how to describe it?”

Fizzy water, potatoes, champagne, ketchup

One of my favourite lists in this book is a crumpled piece of paper that just says ‘String’. Oddly, string features prominently in these lists. Another runs ‘Fizzy water, potatoes, champagne, ketchup’. Mélois imagines this is the list of a demanding celebrity who’s staying at a Swiss health clinic.

The stories are pleasingly left-field. One list features five apples and five tomatoes, nothing else. From this, Mélois unspools a tale of a dead cat and the moment when a child stopped believing in God. Michel’s story revolves around Kinder Bueno, even though the chocolate bar doesn’t feature on the list.

The original source of ‘litterature’

I wonder whether Mélois and Swenson were inspired by the work of Andy Hayes, the tallest man in the 26 writing collective and Managing Director of Quietroom.

Andy started scavenging scraps of paper from the street 16 years ago and subsequently curated an exhibition, Throwaway Lines, where writers and designers created responses to what became known as ‘litterature’.

A day of tragedy

Andy’s quest for litterature started back in 2005, on 7 July, the day of the London bombings. “That evening, there was no public transport,” he explains. “So I walked from my office in Smithfield to Waterloo in a bit of a daze. I realised it wasn’t so far and it seemed like a good way to book-end the day and relax, so I started walking to and from work regularly.

“Shortly afterwards, I was walking over Blackfriars Bridge and saw a scrappy bit of A4 paper where someone had written a rant against racism in a childlike scrawl. What intrigued me was it had a big muddy boot mark on it, so the diatribe against racism was marked by a totalitarian symbol. That was the first piece of paper in my collection.”

Bin day bonanza

Andy carried on filling up a plastic bag with scraps of paper he found on his walks. Roupell Street, a row of Georgian houses near Waterloo, proved an especially fruitful hunting ground. “Particularly on bin day,” adds Andy. “If you’re a seasoned litter picker, one of the litterati, you follow the bin men. If you can bear the smell. People chuck bits of paper away and it flies off in the wind between the wheelie bin and the trash wagon. I’ve got some real gems in Roupell Street.”

Roupell Street in Waterloo: a fruitful source for literary scavengers

It was a red litter day when Andy found part of the draft of a will on Roupell Street. “It was just a lined bit of paper, torn in half. Someone had obviously been working out what to give to different people. Jen will have the jewellery, Betty gets the mahoghany bureau.” Extraordinarily, Andy found the other half of the draft will in the same street the next morning.

“A freak like me could pick it up”

“I found it fascinating that these scraps of paper contained so many little stories,” says Andy. “Every day, we walk past stories and most people don’t even notice them. If you see a piece of paper with writing on it, it could be something mundane or it could be something fascinating.

“Someone’s discarded that piece of paper on purpose or accidentally. It could be washed away in a rainstorm or a freak like me could pick it up and wonder about the story that lies behind it. It only takes a second to stoop down and scoop up a rank piece of paper, but it could contain something amazing.”

He admits he got a bit worried when he thought that litter-picking was becoming a habit. “It wasn’t very hygienic, although I never caught any nasty diseases from it. Luckily.”

Throwaway Lines on show

Andy eventually decided to involve people from the 26 writers’ collective in a project inspired by his carrier bag of abandoned pieces of paper. “We launched the project at Wordstock, the 26 festival of writing, and I stood by a bin wearing a pair of pink marigolds, handing out scraps of paper to writers. Mind you, I think they were probably photocopies, not the originals,” says Andy. “Some people can get a bit squeamish about handling litter.”

The writers created pieces of writing in response to the discarded dockets, missing memos and rain-stained notes. Next, designers produced frames for the litter, elevating rubbish to a new level. The works went on display in a Throwaway Lines exhibition at the Free Word Centre in Farringdon in November 2012. Have a browse and read what Neil Baker did with the story of the will in two halves.

Elise Valmorbida helped run the Throwaway Lines project. She coined the term ‘litterature’ and wrote this ode to an oversized package

A long legacy

For Andy, the spirit of litterature lives on and he is still occasionally tempted to pick up pieces of paper in the street. However, during the pandemic he turned his attention to painting, and is now more likely to retrieve abandoned bits of board and mdf from skips. “I love rescuing old bits of board that have been thrown out, the rougher the better. I put gesso on it and paint over with house paints. I don’t have to be as careful as when I’m painting on expensive paper or canvas. Like Throwaway Lines, it’s liberating to work with stuff that’s been discarded. You can just have fun and it doesn’t matter.”

Before you go

If you’d like to know more about me and my work, here are three ways I can help you:

- Writing appeals, web sites and long-form content for charities

- Providing one-to-one and group coaching in writing for business

- Writing case studies, blogs and other web content for music clients